Hello Everyone,

Welcome new subscribers! Thank you for being here.

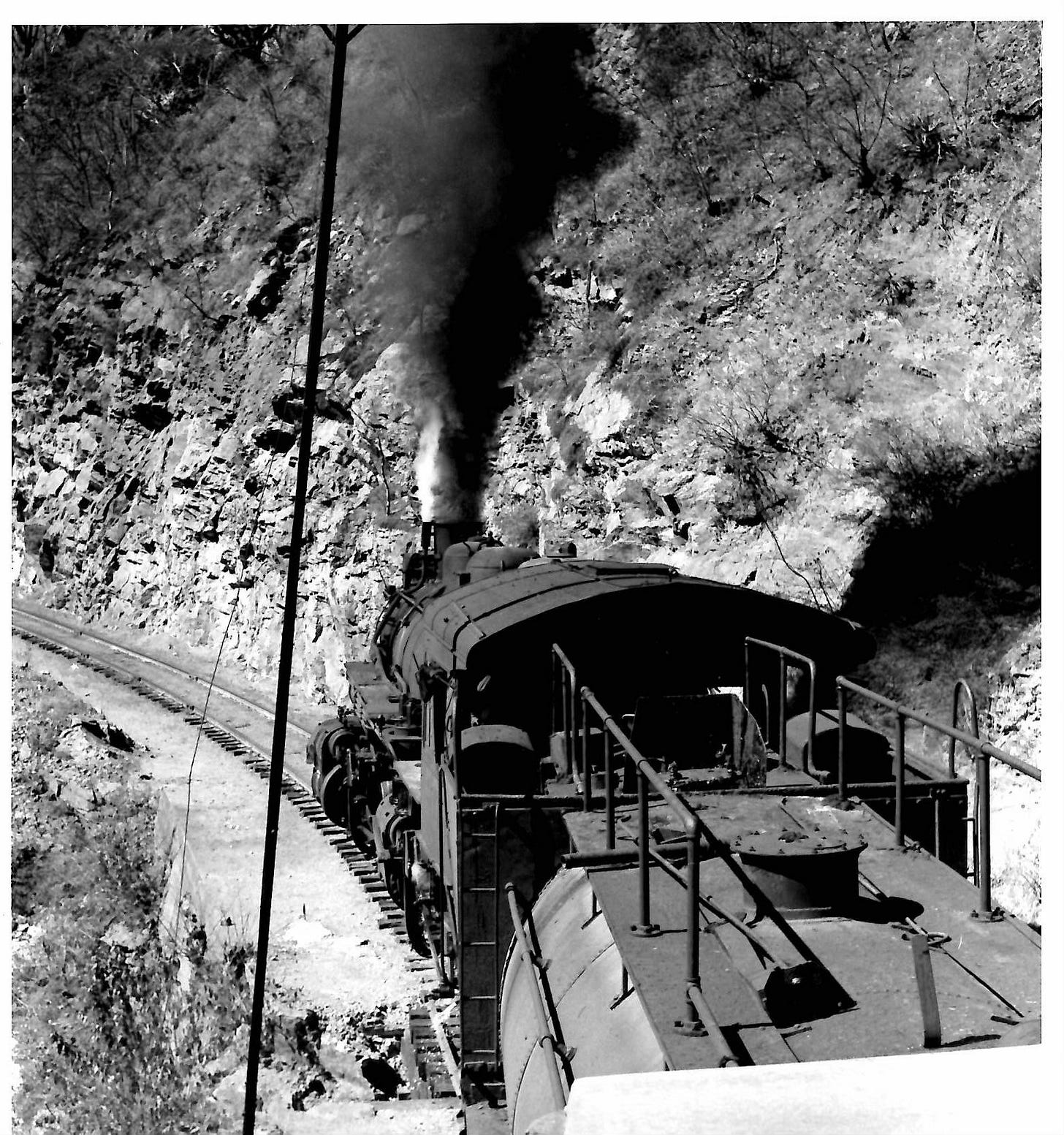

This week I’m posting is an excerpt from the Mexico book my daughter and I are working on. It is the story behind one of my favorite photos which I took while standing on the very slim ledge of a remote canyon on the Oaxaca Subdivision in 1959. (See the fouth picture in this post.) While it is not my best picture, it is one of my favorites because of what I went through to get it. The Oaxaca Subdivision—part of the Puebla Division—traversed some of the most rugged, isolated and spectacular terrain of any railroad in Mexico, on one of the steepest grades.

Here is the full story:

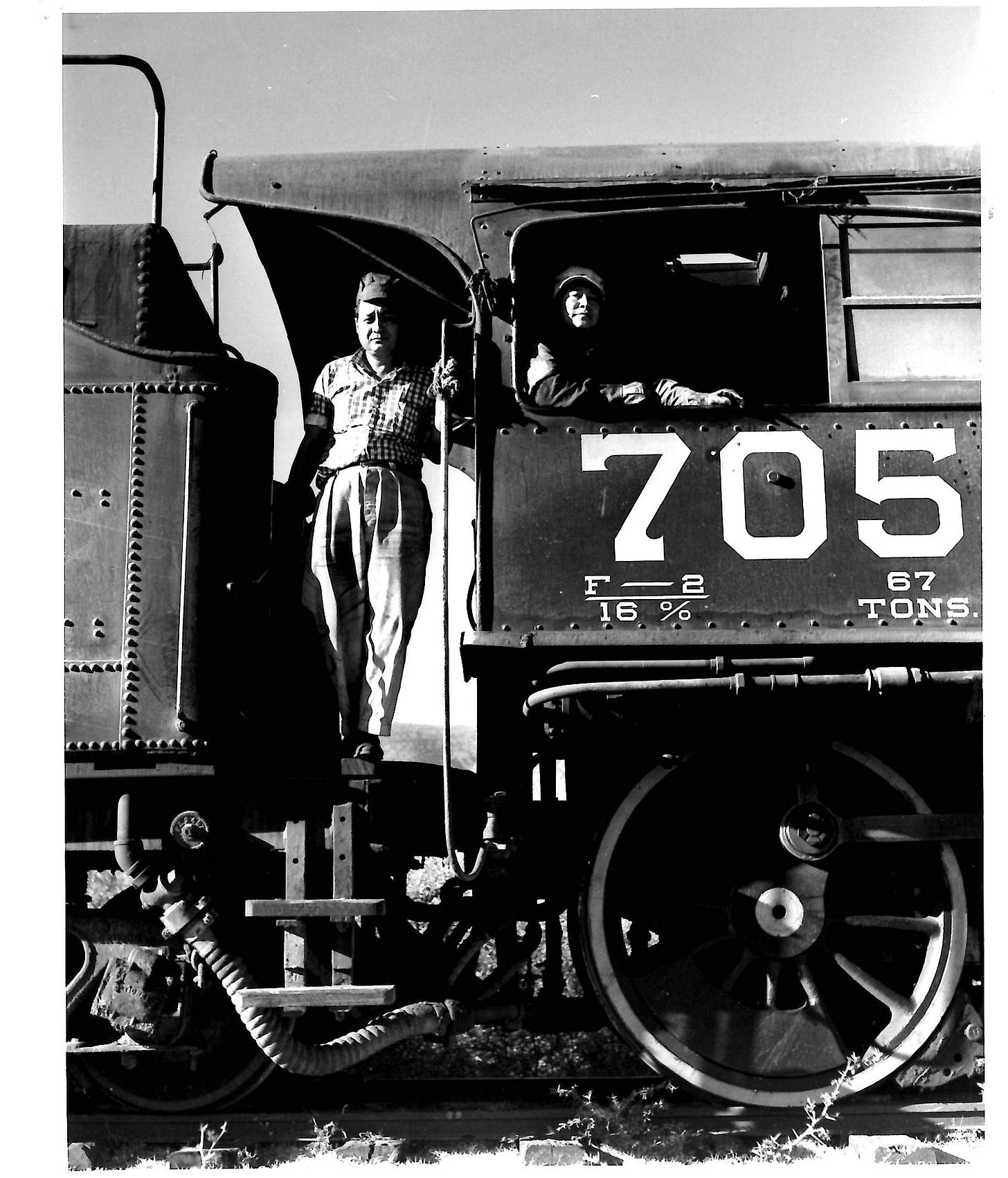

On the day after Christmas, I arrived at the Oaxaca station early to ride the mixed train to Tlacolula. This train made 5 trips a week on an unusual schedule—running Thursday through Sunday, with an extra afternoon trip on Sunday, but with no service at all on Monday, Tuesday or Wednesday. The engine, No. 705, an F-2 4-6-0, was one of the oldest engines I ever saw in service anywhere—it was built in 1880 as one of the earliest engines on the Mexican Central.

I was quickly invited into the cab and I enjoyed the early morning light and the white plume billowing from our stack as the steam condensed in the cool air after our 6:45 am departure. Our engineer serenaded the valley with a multi-toned whistle whose harmonies must have been a marvelous wake up call for anyone still asleep. The line ran 20 miles down the broad, flat Oaxaca Valley, with a maximum grade of only 1%.

Few people boarded on our trip out, but on the way back we picked up small groups huddled at each stop—people crowded toward the car steps carrying baskets, gunny sacks and babies wrapped in rebozos, with an urgency that seemed to exceed even that of a railfan.

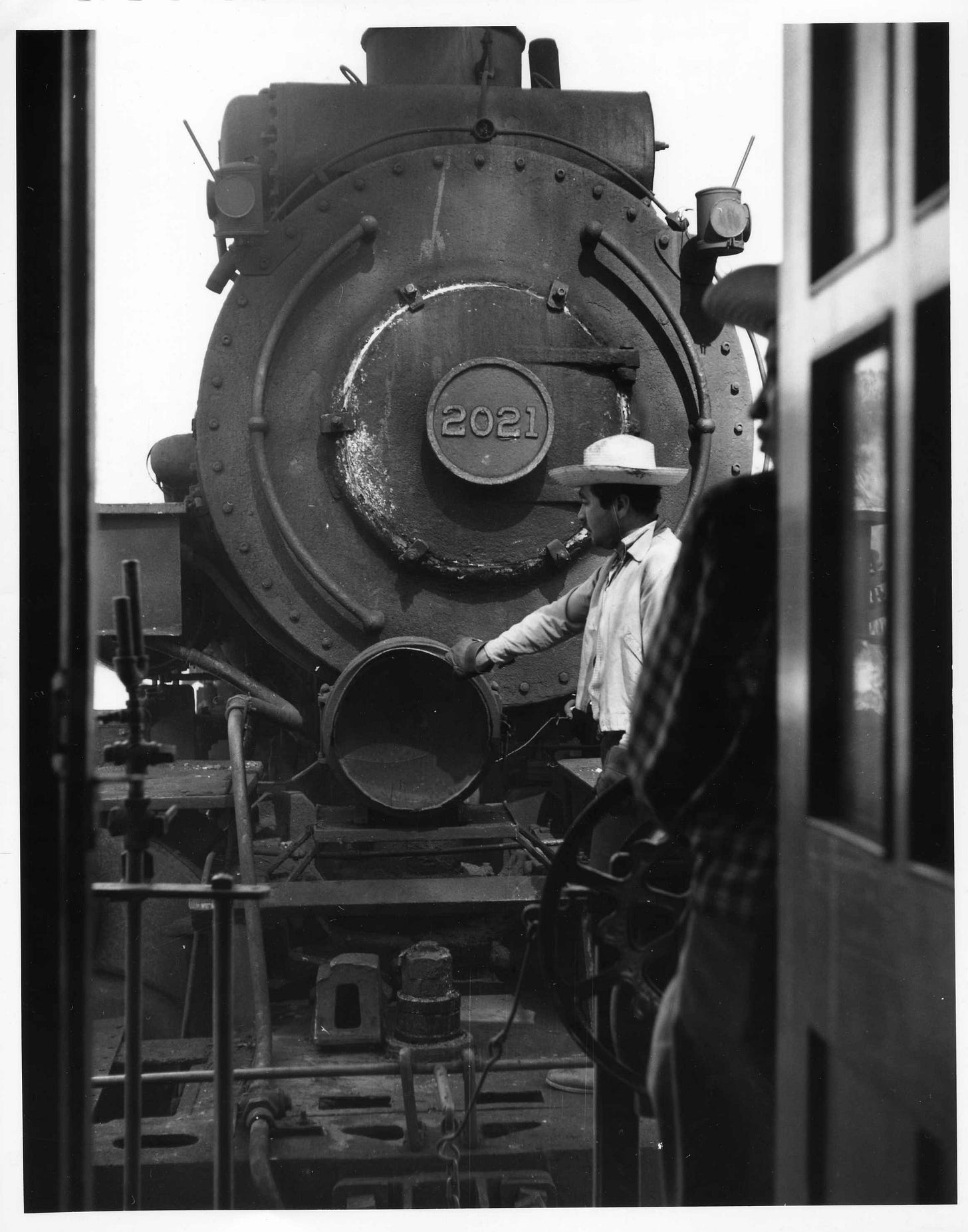

Everyone got off when we got to Oaxaca, but after a 20-minute break our train set out again with the same crew but a new number, this time on the main line north toward Tomellin and Puebla. We ran 22 miles out to Telixtlahuaca, at the foot of the-five -mile 3% climb out of the valley to the 6000-foot Las Sedas summit—the highest point on the line. I set out on foot, passing up the opportunity to ride up the hill on No. 107, the diesel-powered local passenger to Puebla, which arrived a few minutes later. The track twisted upward through deep cuts and across high fills, and before I reached the top I was overtaken by the local freight, led by engine 2021—one of the HR-3 class I had hoped to photograph in action on the Jalapa Division. The 2021 was a compound articulated mallet, with two sets of cylinders and drive wheels. It was older and smaller than the 2031 I would ride out of San Lorenzo the following weekend, and this trip turned out to be my only opportunity to photograph one of the compounds in action.

Arriving at Las Sedas I learned that the 2021 had brought only half its train and would make a second run from Telixtlahuaca. The agent said the southbound local freight from Tomellín would arrive first, so I walked down the grade north of the station to catch it on the hill. I was stopped by a pair of elderly campesinos, dressed in white and somewhat inebriated, who invited me to join them in celebrating the Las Sedas Dia del Santo, the village saint's day. I could hear violin music but I politely declined--I was more interested in a different kind of music that I knew was about to disappear.

Las Sedas was at the top of the most difficult and spectacular portion of the Oaxaca Subdivision--the 40-mile climb through the remote Tomellín canyon, with two stretches of grueling 4% totaling 25 miles, at the upper and lower ends of the 4000-foot climb. There were no roads in the canyon and its several small villages depended entirely on the railroad for transportation.

When the freight finally appeared, I was astonished to see a tiny engine working flat-out to get just three boxcars up the 4%. This engine, No. 900, was smaller than the boxcars it pulled—it had been built for narrow gauge in 1936 and later converted as tracks were widened to standard gauge; it now looked almost wider than it was tall. I later learned that although three mallets were assigned to this section, only one was operational that day—the 2021. The 900 most likely normally worked the Taviche branch, which had a 3.6% ruling grade, but another small 2-8-0, the 930, was working that line on this day.

I returned to the summit and photographed the 2021 making its second run, then begged its crew for a ride down to Tomellin.

I was allowed to ride in the caboose, and we started down with 16 cars, including a company store car carrying provisions for employees along the way with no outside access.

We carefully descended the first 8 miles of 4% to the village of Parián, where small adobe houses with thatched roofs crowded close to the track as if it were the main village street—which in a way it was--there were no roads and no cars anywhere in the canyon. Our engine stopped next to a house with a large clay pot on the ground next to a small table out front. The crew disappeared inside for their afternoon comida, the big meal of the day in Mexico.

After nearly an hour we continued our descent. We were now clearly following a stream, the Rio Salado, in a deep valley, which in a few places opened wide enough for cultivation. At one point I saw a man and little boy walking from a thatched hut toward their well-tended field. It looked like a nice place to farm—but, oh so isolated! Most of Mexico's rural population lived in small villages; did that little boy have any friends?

After Venado the nature of the canyon changed. The grade got serious again—16 miles of 4% from here to Tomellín. The canyon walls closed in with vertical cliffs on one side opposite steep slopes studded by majestic organo cacti. At the bottom of the gorge there was nothing but the railroad—no room for farming or anything else except the small stream responsible for the canyon’s formation. It looked innocuous enough now, but during the railroad’s first rainy season in 1893 the Salado washed out so much track that the line had to close down for several months while the track was re-laid at a higher level.

I began to look for good spots to photograph the train the next day and spotted a few. When we finally arrived at Tomellin, I was allowed to spread out my sleeping bag on one of the caboose bunks for the night and I slept soundly, not even hearing the nocturnal diesel-powered passenger trains to and from Mexico City.

The next day I got up early.

I had picked out two particularly dramatic spots from the caboose I’d ridden on the day before, and the closest was several miles up the grade near Organal. I set out before the sun had come over the mountain--I wanted to get there in plenty of time to select the best angle, or to continue to the second spot if the first wasn’t satisfactory. The sun’s rays were just reaching the rails in the bottom of the canyon when I heard something coming down the hill. To my surprise, it was the 2021, returning light (alone) after helping the night passenger train up the grade. What a show that must have been!

When I got to my first spot, bright sunlight illuminated the vertical cliff I had noted the evening before and it looked even better than I remembered it.

I tried various angles and finally decided I needed elevation to capture the scene adequately, including the water in the Rio Salado. I saw what looked like a ledge 20 or 30 feet up the cliff and managed to scale the rock to get to it. It was several inches wide and several feet long--too narrow for sitting, barely wide enough to stand on. (I couldn’t even place my feet facing forward, I had to turn them sideways.) But the view was fabulous!

Since scaling the cliff had not been easy, I decided not to go back down—I didn’t want to have to climb under duress if the train should come before I was ready. So, I waited, taking in the view. It was peaceful—no sound but the rushing of the brook and sometimes a faint shush of the wind. I heard occasional rustles nearby as small iguanas scurried up and down the rock face tending to business on toes that must have had suction cups. The brook’s gurgle varied with the vagaries of the wind.

I waited—and waited—and waited some more.

A large black vulture soared in great lazy circles above, taking in the entire scene—but told no one what he saw.

I enjoyed the peace and solitude. After an hour, though, I felt it would be nice to sit down--but the ledge was too narrow.

After two hours my legs were protesting. I was tempted to climb down to give them a break but did not--by this time there was considerable risk that the train would come before I could get back up. I began having trouble distinguishing sounds--was that rhythmic beat the 2021 approaching far down the canyon—or just my own heartbeat, which seemed to get louder and louder? I checked and rechecked the camera’s lens opening, shutter speed and most of all, the focus. And I stood in solitude on my narrow ledge and waited--and waited some more.

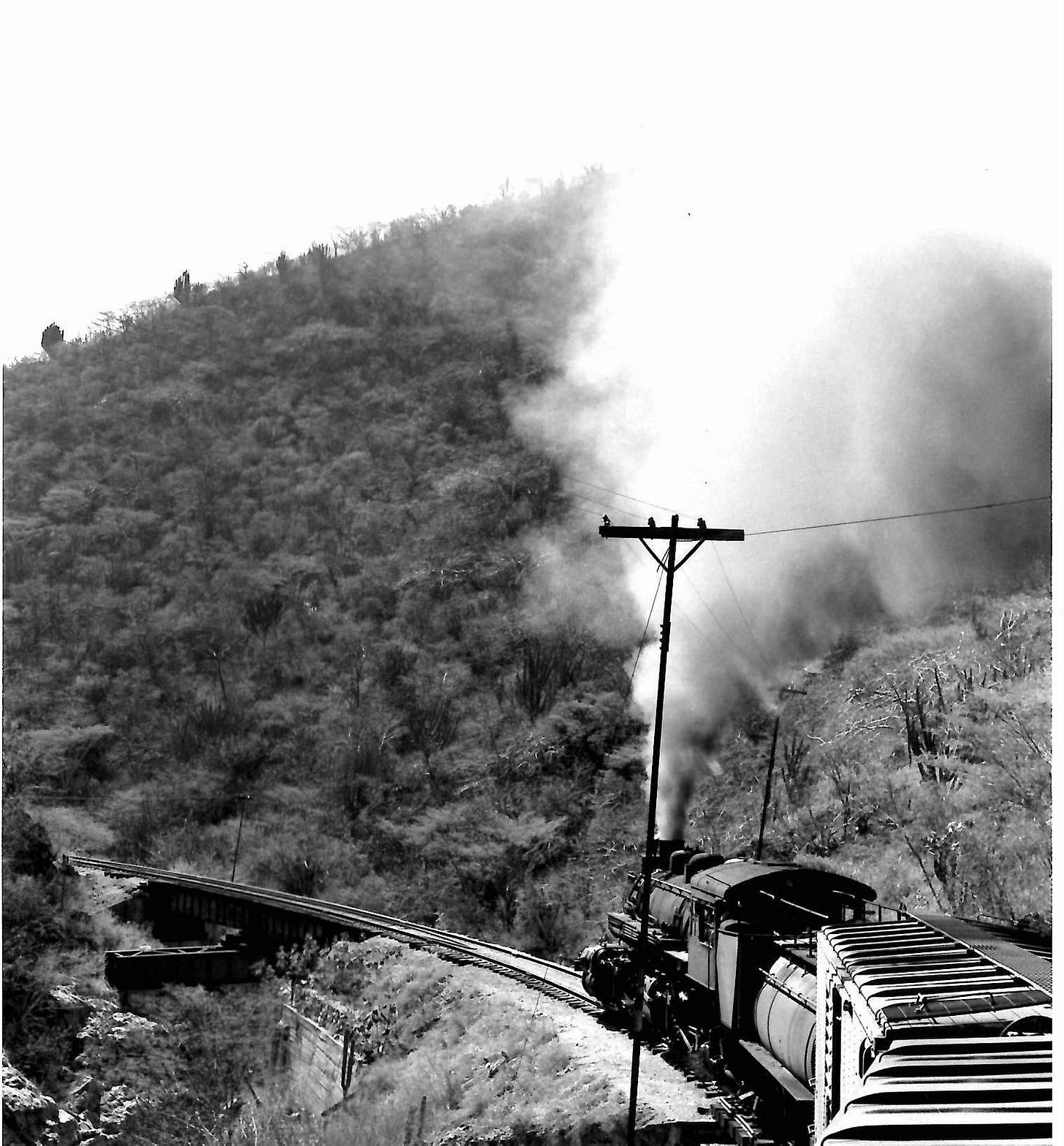

Finally, after two and a half hours, I heard a new rhythm—faint at first, then more distinct—and finally smoke appeared above the promontory around the bend! My adrenalin started pumping--and at last the 2021 came toiling around the rocky shoulder, hurling a furious black plume straight upward—all twelve drivers struggling to pull their load at the speed of a tired jogger. One by one, nine boxcars slowly came into view as I waited for the exact moment to trigger the shutter. At last, the caboose emerged, with the two brakemen seated comfortably atop its cupola, enjoying a view any railfan would have died for—and these brakemen got paid to see it!

At the proper instant I clicked the shutter and captured everything—the vertical cliff, the 2021 and its ferocious plume, the deceptively innocuous looking Rio Salado and the spiny cacti on the opposite slope.

Then I quickly descended and reached the ground as the boxcars were still passing laboriously by. Their temptation was too great to resist—I hung the tripod from my belt, slung my backpack over my shoulder and with my Rollei hanging from my neck, I climbed to the top of one of the cars as they slowly advanced. I hoped the crew would not be offended—at some level I sensed a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. From the top of the boxcar I proceeded to record the drama as the 2021 toiled upwards, crossing and re-crossing the Rio Salado.

Suddenly, a miracle happened!

The 2021 lost her footing, her drivers spinning wildly and we almost stopped. I ran forward along the boxcar catwalks, took a shot from behind the tender:

then dropped down the ladder to the ground and ran ahead. The engine was still moving but barely, and its sound was deafening, intensified by the close canyon walls. I spun around, refocused and took another shot capturing the 2021 with its turbulent plume against another sheer rock wall, this time close up from ground level.

When we finally reached Venado the boxcars were dropped into the siding and the 2021 backed down to the lower switch to retrieve the caboose. No one said anything about my antics and I was again allowed to ride back down on the caboose platform. We stopped for water at a lonely siding called Almoloya.

When we reached Tomellin, I took a farewell photo of the crew and then waited for No. 107, the daytime passenger to Puebla.

It was a Christmas vacation very happily spent.

What a story! And what beautiful pictures. Thank you! xxx

These stories are fascinating! I love how I am transported back in time to experience these adventures with you. The photo of the 2021 coming around the bend is spectacular, but made even more special knowing the lengths you took to capture that moment! Thank you!