Custom Made Whistles and the Midnight Express

PLUS--a bonus! A sweet memory from the candy maker at the Acámbaro railroad station.

On the Tultenango District, passenger engines were assigned to particular runs until they came due for repairs. Since engineers bid on these runs according to seniority, they developed a sense of ownership of their engine not unlike that of the senior Querétaro Division engineers. Although the adornments were not as colorful as those on the Niagaras, stars and smokestack crowns decorated some of the Pacifics. The real measure of an engineer’s status though, was his whistle. Some of them reminded those of us from the U.S. of the deep chords we had known on the Southern and N&W engines in Virginia. These whistles were not supplied by the company—they had been custom made for senior engineers by highly skilled shop craftsmen many years before, and their esteem among railroaders was comparable to that of the finest Paracho guitars among Mexico’s best musicians.

By 1960 most of the old whistle makers had passed away, but their music lived on, coursing across the plains, the pride of the men who played their chords. Some whistles had been passed from father to son and since they were personal property, one learned that the whistle tones identified the engineer rather than the engine.

The Midnight Express

One of these magnificent whistles belonged to Chavo Obregon (not his real name) who ran Nos. 27-28, the night express between Toluca and Acámbaro. One frosty winter night in 1961 I rode north with Chavo in his engine, No. 2520. The train was due to leave a few minutes before midnight and when I arrived at the station several engines were steaming softly in the open shed across the tracks. But beyond the platform the flashing glow from the firebox silhouetted a tender. The irregular firebox roar and the occasional thud from the air pumps shook the ground as I approached. Chavo and his fireman were going over the 2520’s running gear with grease pump and oil can. As I joined them, we were enveloped in a soft cloud of strangely sweet-smelling steam issuing from the open cylinder cocks—a comforting relief from the cold.

The oiling done, we all climbed to the cab to await No. 27’s arrival. Chavo took advantage of the remaining minutes to polish the dimly lit gauges on the backhead sheath. They were already well polished, as were the various brightly painted faucet handles that controlled the sander, bell, headlight dynamo and other essentials. The irregular roar of the firebox, the faint hissing of leaking steam, the smell of hot grease, the whine of the dynamo, and the steam pressure needle sitting just below the pop-off mark—all conveyed a sense of anticipation and energy—of a great force, barely contained. In the surreal midnight darkness, it was hard to remember that No. 2520 was merely a machine—a manifestation of the laws of physics and nothing more.

Suddenly my reflections were interrupted by a discordant “baahh” --No. 27’s diesel was announcing its arrival. It was the only diesel operating on the Pacific Division that night—and how different it was from the world of steam it invaded! Its cab offered plush swivel seats and an unobstructed forward view through a windshield with wipers—an even hum came from motors hidden behind painted sheathing as if exposing their energy source would have somehow been immodest. Such a machine was operated by fingers rather than brawn, and a flashing light was needed to inform of slipping wheels. Gauges and indicators provided data that steam engineers absorbed from sound, intuition and years of experience.

Chavo eased the throttle out and we moved slowly backwards until the tender coupler gently locked into that of the baggage car. The conductor appeared from the telegraph office with only a yellow clearance card--there were no orders and the railroad was ours to Tultenango.

A few minutes after midnight a lantern was raised and Chavo’s whistle sounded two quick melodious blasts. The 2520 walked through the yard with cylinder cocks open to clear water from the cylinders that had condensed from leaking steam during our wait—then the engine widened her step as we passed the last switches. The rails shone straight and clear ahead in our headlight’s glare.

A silvery bus was overtaking us on the highway to our left. The road crossed our tracks ahead and Chavo did his stuff—the familiar two longs, a short and a long crossing warning, which was completely lost in a spirited series of extra wails he threw in. The bus prudently stopped and we raced across the highway, white steam trailing behind.

It occurred to me how much more efficient the buses were for moving passengers than the train. They ran at frequent intervals, sometimes every 15 minutes, and they usually made much better time. The ability to travel at the customer’s convenience rather than the railroad’s, provided a major savings in time. And the cost of maintaining and operating a ponderous steam locomotive compared to that of the 6-cylinder Cummins that fit neatly beneath the bus driver’s seat--it all made No. 2520 and even the train itself seem rather improbable.

Nevertheless, we roared through Tunnel No. 3, past the Toxio marker and a few minutes later Chavo pulled the whistle cord again. A long, multi-toned moan coursed across the lonely prairie, announcing our approach. Chavo looked back to see a lantern raised and lowered at one of the vestibule doors behind. He sounded his whistle again to acknowledge the conductor’s signal that we had no passengers for Ixtlahuaca—a flagstop for No. 27. Then he eased back the throttle as the solitary station came into view—but no one appeared on the platform to wave us down.

The throttle came out again and we thundered past the little station. We glimpsed small section crew huts next to the track, closed up and dark for the night. Men, women and children safely asleep inside—surely they must have heard us—what did they think? Then out onto the open plain again with only an occasional cactus to catch our headlight’s beam.

We approached Acámbaro not long after 4AM and Chavo gave his last concert of the trip, a long blast on his magnificent whistle to announce our arrival in Acambaro. As we slowed to our final stop, we were met by an army of car inspectors with their oil buckets, and a man with a baggage wagon. They disconnected the 2520 for the replacement engine, unloaded and loaded luggage and checked everything in the back, adding oil where it was missing, and then closing each plug with a loud “clack.” “Once I didn’t whistle,” Chavo told me, “and when we arrived, everyone was asleep.” —and when we got in, they were all asleep!”

No. 27 and the 2520 may have been an inefficient way to move people—but what glorious inefficiency! And how lucky I was to experience it on board the beast itself!

* * *

From Frank’s Daughter Rebecca:

We also wanted to share this piece we received from our friends at Amigos del Ferrocarril, in Acámbaro, Mexico.

It is a memory of Dad’s first visit to Acámbaro from Don Pantaleón Tinajero, who was the official candy maker at the Acámbaro Railroad Station for over fifty years. Anyone who knows Dad and knows how much he eats (tremendous amounts!) and especially how much he enjoys sweets (we call him the cookie monster) will not be at all surprised that he made an impression on the family that owned the candy store.

Here it is, as told to by Sr. Pantaleón’s family. We are so delighted to have this piece. Many thanks to the Tinajeros for this story!

An Honest and Brilliant Young Man.

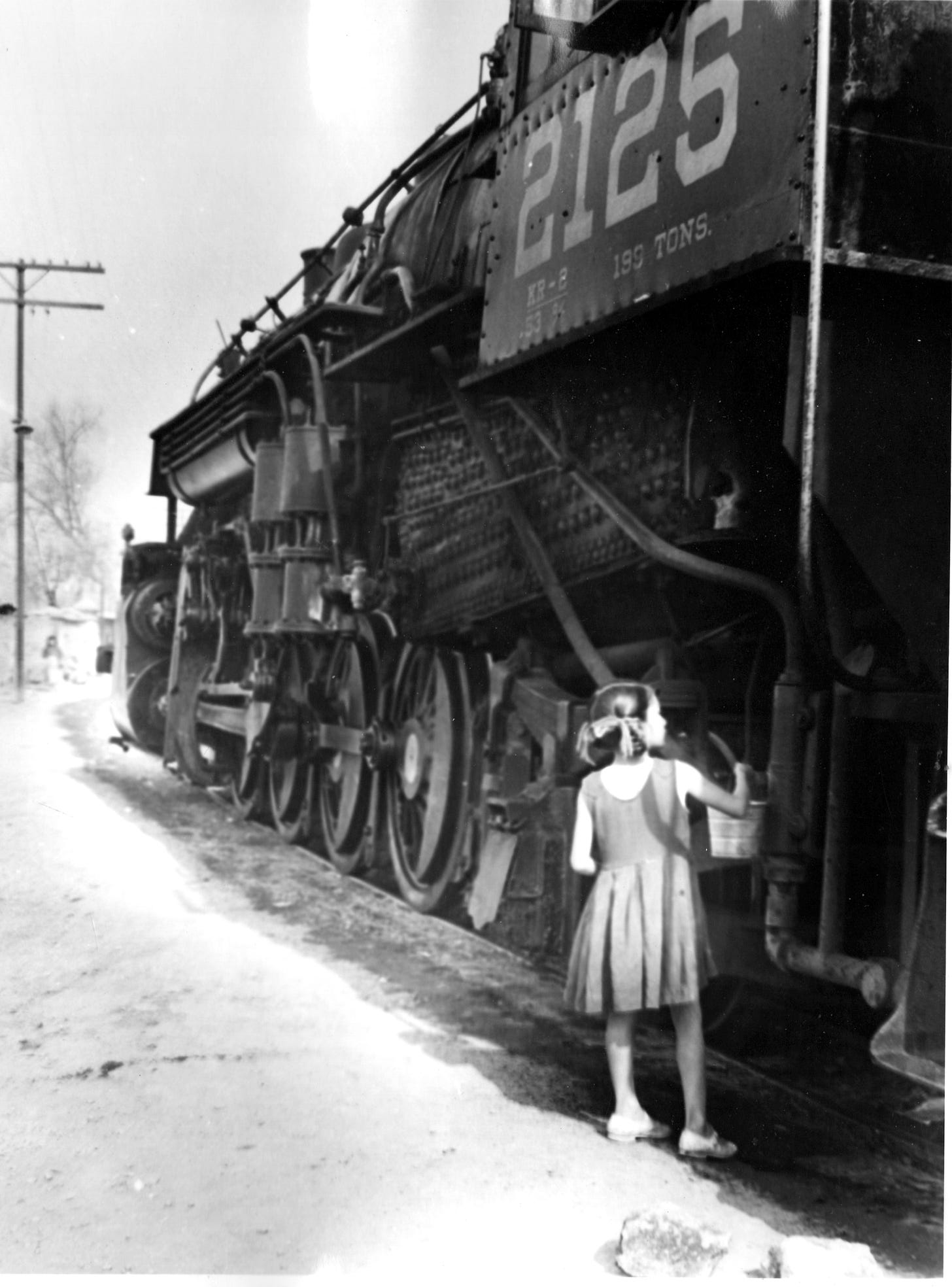

The young artist came to our town in the late fifties of the last century. He arrived on the train from Mexico City, looking for the last engines from the golden age of steam. He got out of the passenger car with a backpack and his camera tightly pressed on his chest, as if it were a baby he needed to protect from life’s harm. When he saw Las Prietas Lindas (the “pretty dark ones,” as we called them) resting on the rails, his face lit up.

He was at Acámbaro, in the state of Guanajuato, in the Pacific Division of the National Railways of Mexico. It was one of the few divisions where steam locomotives remained active as support for the newly arrived diesels which were, without a doubt, more efficient.

The steam engines were forty or fifty years old, but they were well-cared for by most of the people who worked on them, many of whom had serviced them at some point in their lives.

It is important to note that the only two steam locomotives built in in all of Latin America were assembled in Acámbaro: the NdeM 295 called Hermana Mayor (built in 1942) and the NdeM 296 called Fidelita (built in 1944). This was significant because Acámbaro was the poorest railroad workshop in the country during this time: they didn’t have the specialized machines that other shops like Aguascalientes had. But the workers there had and an inventiveness and affection for steam. They crafted their own tools and small machines to repair and maintain the engines and developed their own molds, so that when parts or tools broke they could create new ones. (When supervisors from the Aguascalientes workshop came to Acámbaro, they were impressed by what the local workers were able to do without sophisticated machinery. “In Acámbaro,” said the local foreman, "we work with the soul and heart as our best tools.")

For this reason it was called the “artisan railroad workshop” for almost thirty years (from the forties to the sixties.) It was, to put it politely, a last bastion for these engines before their final journey to Huehuetoca, also called, “The pantheon of steam locomotives.”

And this was why the Young Artist traveled to our town: to meet the last living locomotives. And boy, was the trip worth it!

Don Pantaleón, the candy-maker was seated on a metal bench over the railway platform at the station. At his side was his famous cart full of candies well-known in the Pacific Division: cocadas, custard, and of course, the goat milk “cajeta” in all its variations.

The arrival of the young photographer struck him because few gringos got off the railroad train in town and those who did usually only wanted to use the bathroom. But this man was different. He had a hint of intrigue that was noticeable immediately. Erendira was fresh out of the roundhouse, waiting for the crew to go out on duty. (All the Mexican engineers used to give names to their engines. In Mexican railroad vernacular, people used to say that the Prietas Lindas received more caresses from their drivers than a man would give to his wife. And it was true. Many of the engineers spent more time with their engines than they spent with their wives and families. And these locomotives were jealous, too!)

The young man saw Erendira, only a few feet away, launching her signal—a white, almost transparent tail of steam—into the sky, and his face transformed! He approached the engine and started taking photographs, not only of the gigantic machine, but also its crew members, who, ready to begin their shift, exchanged shy smiles and looks of surprise when they saw him approaching them. Don Pantaleón smiled as he watched the workers posing for the young gringo’s camera. Although the railroad workers were rough, they also had their relaxed side. He watched them shake hands—new friends—and turned his attention back to his work. While the railroad convoy left for the Michoacán, the expert candy maker tended to his customers.

Soon, the young man approached his cart and asked, in polite Spanish,

“Aun tiene natillas, Amigo?”

(“Is there any custard left, my friend?”)

Don Pantaleón was the first person in Acámbaro to invite Frank Barry to his home. There was an age difference of six decades between them, but that didn’t stop them from building a friendship that lasted until the candy maker died five years later.

When Frank Barry visited the family home, just around the corner from the railroad station, he enjoyed his first spicy Mexican meal in Acámbaro— “mole ranchero,” with freshly made tortillas.

Miriam, Don Pantaleón’s granddaughter remembers: “Frank was hungry, and when he was given the mole dish, he took a tortilla, rolled it, and began to eat! The mole was not too spicy for us, but for his tastes it was very hot. He was suffering—his mouth and throat were burning! My grandfather had to give him a cold pulque jar.”

She continues, “My grandmother was enchanted with Frank because he enjoyed our candies and always paid for them. She tried not to take his money, but he always said, “Señora, si no recibe mi dinero, entonces me llevaré la tienda completa!"

(“Madam, if you don’t take my money, I will clean out your entire store!”)

He didn't accept the invitation to stay in Tinajero’s house out of politeness—there were young women there, so he went to a hotel downtown.

He returned to Acámbaro several times, always looking for las prietas lindas.

And that was great for our local railroad tradition because due to his artwork, we can enjoy, half a century later, the great memories of the steam locomotive golden age in Acámbaro that his images captured forever!

Lovely.

Another intriguing and beautiful story - really bringing out the human side of railroading and village life.