I first visited Yucatan in April, 1960, with my mother. We planned the trip to accommodate both our interests—seeing some of Yucatan’s famous Mayans ruins and other tourist attractions (my mother), but traveling by train as much as possible to get there (me). The Chichen-Itza ruins were easily accessible by Valladolid buses that went right by the site, but as we were going by train, it took a lot longer. It also required getting up very early and riding all the way to Valladolid, then riding a bus about 15 miles back toward Merida to reach the ruins. But my mother loved adventure and was a good sport, so she agreed.

Although Valladolid was the largest city in the eastern part of the peninsula, it lacked direct train service; we had to board narrow gauge train No. 31, bound for Tizimin, and change to a branch-line train at the remote Dzitas junction. All the narrow-gauge cars were wooden and we rode second class on wooden seats with open windows. The car was well filled and most of the women wore the starched white Mayan huipiles with bright colored embroidery around the neck, sleeves, and hem that were standard in rural Yucatan then. Most passengers conversed in Mayan; Spanish was their second language.

We passed field after field of henequen, but as we got farther east the henequen gave way to forest and at times branches slapped into our open window. At Dzitas we found a two-car train inside a stone walled enclosure headed by a small 4-6-0 numbered 47 with a giant bonnet smoke stack. It burned wood rather than coal or oil, and the tender was piled full of logs.

This was an exciting find! It was the last wood-burner on the railroad; I was told it continued to burn wood to use up ties from the narrow-gauge line through Motul that was then being torn up. I had seen wood-burners on a couple of logging operations in the U.S., but never on a passenger train. While I had ridden in the coach with my mother for most of the trip, the chance to ride in a wood-burning engine was a once in a lifetime opportunity I couldn’t resist! I talked with the grizzled engineer and ended up riding in the cab.

The fireman was a wiry, friendly lad who appeared younger than me. The firebox door was small–not much more than a foot in diameter. He threw logs into the opening with uncanny accuracy–I didn’t see him miss once. The engineer was much older, wore a somewhat baggy hat and goggles. I soon found out why.

April is brutally hot in Yucatan and the front doors of the cab were open for ventilation in addition to the side windows. But this had a major disadvantage–while the stack contained multiple spark arresters not needed by coal or oil-fired engines, they didn’t really work, and the cab soon filled with sparks and even occasional glowing chunks from the burning wood. Dodging them was a nuisance and not always successful. It was a wonder that the wooden cars behind us didn’t catch fire –and that the forest itself didn’t ignite -- we were in the last month of the dry season.

At the first station, in the small village of Uayma, the engineer disappeared. The fireman, without a word, sat down in the engineer’s seat, released the brakes, shoved the reverse lever forward and pulled out the throttle. We began to move. I was astonished by this—where was the engineer? We were in a rural forest with no towns. I didn’t ask questions but took the fireman’s seat and kept trying to dodge the sparks. The fireman periodically got up to throw in logs, which left me as the only one watching the track ahead. This didn’t seem very dangerous because the track was absolutely straight and there were no grade crossings. In fact, there were no roads at all–this train was the only connection with the outside world for the three villages between Dzitas and the end of the line at Valladolid.

At the next stop, I decided I wanted a picture so I got off and went up to get ahead of the engine and there, sitting above the cowcatcher was not only the engineer, but also the conductor! Both of them had had it with the sparks and found this a more pleasant solution. I had never ridden on a cowcatcher—I had always dreamed of it; my uncle had told stories about traveling this way in California during the depression. I asked the engineer if they could move over so I could join them--which they did. Soon we were underway and I saw the track from an entirely new perspective. We were much closer to the ground and we had absolutely no protection in the event of any mishap--but we were free from the sparks!

After a while it seemed to me we were going faster than before. I leaned over and yelled to the engineer, asking our speed; “Uno!” came his quick but puzzling reply. Uno? That's “one” in Spanish. I was totally perplexed, yet didn't want to show my ignorance. But finally, my curiosity won out: “One what?” I shouted back after a long pause.

“Un kilometro por minuto!” That works out to about 35MPH–not an unreasonable speed for a narrow-gauge train. But to me, with my feet less than a foot above uneven rails, all but obscured by weeds, it seemed plenty fast! But we arrived in Valladolid without mishap, the engineer, the conductor, and a gringo out on the cowcatcher.

When I next saw No. 47 on my way to Belize and Guatemala a year later, it was being converted to oil in the Merida shop. I realized that I had ridden on the very last wood burner in passenger service in North America during its last year burning wood!

* * *

POSTSCRIPT

Last winter when my daughter and I were working on this chapter we found, on the bookshelf in the dining room, a slim black book that turned out to be my mother’s diary from her trip to Yucatan.

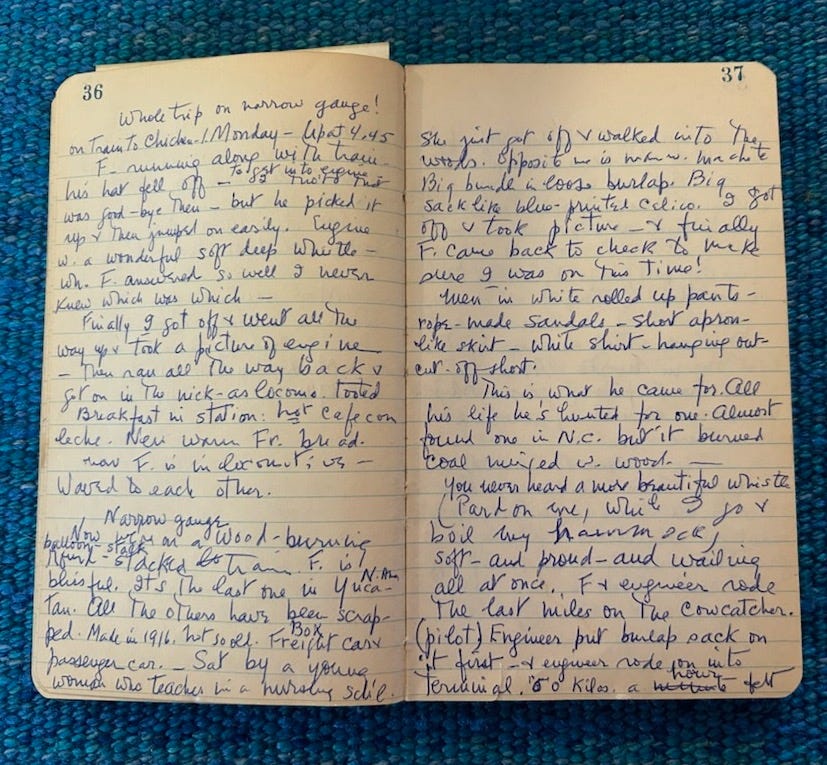

We opened it up and there, on p. 36 and 37, were her notes from this particular ride!

We were so excited, and reading about it from her perspective brought tears to my eyes. Here is an excerpt—F. is Frank (obviously):

“Whole trip on Narrow gauge! Up at 4:45. F. running along with train to get into the engine. His hat fell off—I thought that was good-bye, but he picked it up and then jumped easily on the train. Engine with a wonderful soft deep whistle—which Frank answered so well (from his own throat) I never knew which was which…Breakfast in station: HOT cafe con leche and fresh warm French bread. Now Frank is in the engine. We waved to each other.”

* * *

“Now we’re on a wood-burning ballon stacked train. F. is blissful. Its’ the last one in Yucatan, all the others have scrapped. Made in 1916. Not so old…Sat by a young woman who teaches in a nursery school. She just got off and walked into the woods. Opposite me is a man with a machete…a big sack like bundle of blue printed calico. I got off and took a picture and F. came back to check on me, this time to. make sure I was on !

This is what he came for. All his life he’s hunted for one. Almost found one in N.C. but it burnt coal mixed with wood. You never heard a more beautiful whistle! Soft and proud and wailing all at once. F. & engineer rode the last miles on the cowcatcher. Engineer put a burlap sack on it first and they rode into the terminal at 35 mph. ‘Felt really fast out on the cowcatcher,’ says F.”

Which uncle was it who talked about riding on trains in California during the Depression?

Wonderful!